“The Reformers did not see themselves as inventors, discoverers, or creators. Instead, they saw their efforts as rediscovery. They weren’t making something from scratch but were reviving what had become dead. They looked back to the Bible and to the apostolic era, as well as to early church fathers such as Augustine (354–430) for the mold by which they could shape the church and re-form it. The Reformers had a saying, ‘Ecclesia reformata, semper reformanda,’ meaning ‘the church reformed, always reforming.’”– Stephen Nichols (Historian)

I mentioned in my first post in this “series” that I, and I feel like many other people, feel a need to get back to the early church. To restore something that has been lost. Frank Viola felt that way and his solution was organic church. I didn’t mention it in my last post, but that was really what the Restoration movement was all about as well. And as you see from the above quote, it’s also what the Reformers were all about, and from their efforts, we got Reformed theology, and more generally the Protestant church. So clearly this sense of needing to find the early church is strong among many Christians. But the Reformation was now over 500 years ago, so evidently they didn’t figure it out. I’d imagine to some degree nearly every Protestant denomination (and non-denomination) represents at attempt at restoring the true way of doing church.

At the time and place of the Reformers, there was only one church, the Catholic church (the Eastern church existed as well, but they were completely cut off from each other. If you were a Christian and you were in the West, you were Catholic). As you’re probably aware, the Reformation is generally considered to have begun with Martin Luther nailing his 95 theses to the doors of Wittenberg. What this represented, really, was a call to debate the practice of Indulgences, which, along with the notion of Purgatory, was a medieval invention of the Catholic church, and quite clearly a way to make money off of the faithful. It’s not too different from a lot of those TV evangelists, I suppose. It was never Luther’s intent though, to break away from the Catholic church. He sought to change things from within. It wasn’t until he was excommunicated that he just sort of embraced it and started what ultimately became Lutheranism.

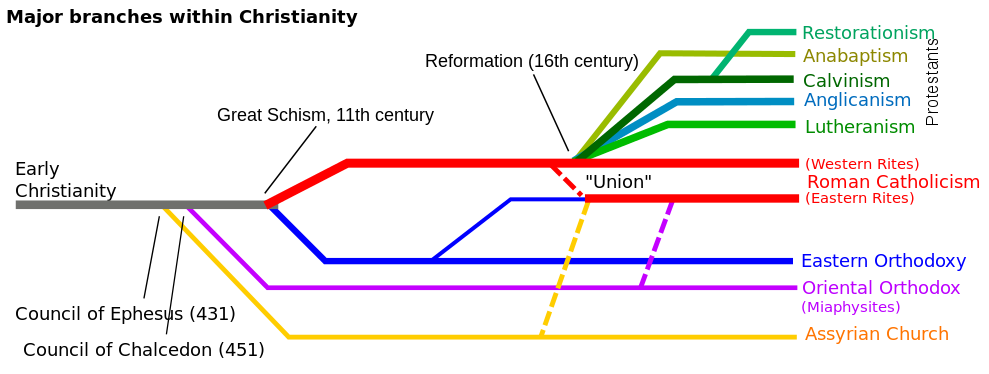

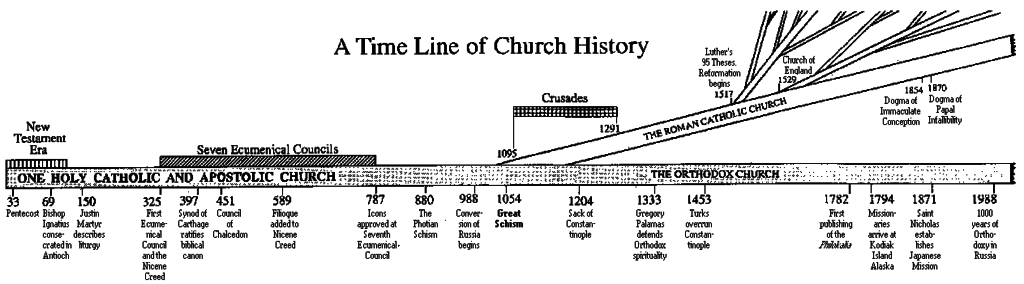

So, since we’re interested in the early church, let’s take a look at a high level timeline:

Now, on a timeline like this, “Early Christianity” looks pretty nebulous. What does that mean? The timeline above is a pretty typical layout used by Protestants. If you go to Catholic or Orthodox sources, it differs a bit:

Note that the different between getting this from a Orthodox perspective or a Catholic perspective will change whichever church continues on the straight line, and which one branches off.

The text is small, but note that the First Ecumenicial Council was in 325, and is where the Nicene creed was first developed (finalized at the Second Ecumenical council). The Biblical canon was established by the 5th century. All of this is happening during that nebulous period.

So why did it take almost 300 years from Pentecost to have a council to establish a creed? Did Christians just not know what they believed for 300 years? The real problem is that for 300 years the church was forced to largely operate underground in the Roman empire. The Church was able to establish itself somewhat even in the very early days we see recorded in the New Testament, but it wasn’t really until Constantine, the first emporer who was really friiendly to Christianity, came to power that they were able to operate more freely. Note that I’m not a historian and even with that caveat, I’ve only got a high level view of the history of this era, and I may be simplifying this. Nonetheless, all the Church structure that many Protestants don’t seem to like, such as Bishops and Patriarchs, etc, were all pretty much established in the first 500 years. A lot of Protestants object to “priests”, but that title was in use by the 2nd century.

All of this is really just to say that there was a real and unified Church during this time period. Yes, there were heresies, and there were some schisms, but the Church was largely united up until 1054 AD (though the seeds of this had probably been in place for awhile before it officially happened).

Here’s this relatively short but helpful video (Made by a Catholic, but it seems to me like it’s a pretty fair treatment)

There’s plenty more to be learned about the Great Schism, but, I’ll suffice it to say that in my opinion it seems to me that the Bishop of Rome was the one who forced the split, and that it was largely because of his insistence that he should have more power. And I do think that Catholics seem to have added a great deal to the faith – and that those were in part things that led to the Reformers wanting reform, and also in part things that forced further schism as how do you argue against Papal supremacy from within? If one guy has all the power, how do you affect change?

I think that Protestantism was probably the logical end of Roman Catholocism, and I think that the endless denominations and non-denominatiions of Protestantism is the logical end of Protestantism. And I don’t think it’s a good end, because the prayer of Jesus was:

“I do not pray for these alone, but also for those who will believe in Me through their word; that they all may be one, as You, Father, are in Me, and I in You; that they also may be one in Us, that the world may believe that You sent Me. And the glory which You gave Me I have given them, that they may be one just as We are one: I in them, and You in Me; that they may be made perfect in one, and that the world may know that You have sent Me, and have loved them as You have loved Me.”John 17:20-23

Christians are hopelessly divided, and that almost entirely comes from the seeds of the Reformation. The Reformation still strikes me as being necessary, and yet, the consequences are very dire.

All that being the case, it seems to me there is a very strong case that the Orthodox church is, as they would say, the fullness of the faith. That it has continued unbroken and in unity since the beginning of the faith. And so, I’m deciding to give Orthodoxy a try. I almost want to use stronger language than that, but I’ll be honest, I’m still in the early days of entering it… I’ve only been into an Orthodox church one time so far, after all.